I did a solo run of the notorious Viking Circuit for my most recent birthday and it literally1literally literally almost killed me.

But there’s no way the story would make the AllTrails character limit, so here’s a whole blog instead.2 A great creative debt is owed in particular to Kevin from Goin’ Feral One Day At A Time and Greg from Hiking Fiasco for their special brand of informative storytelling. And an additional thank you to Kevin for responding very promptly and helpfully to a Facebook message when I reached out to him earlier this year about this hike!

The Viking Circuit is a ‘grail hike’ for me. I completed it in November 2023 for my birthday after spending that year’s green season doing other walks in the Victorian Alps in preparation. The goal was to get to a point where I felt comfortable doing the walk by the time the winter gates opened again around Cup Day.

I’m glad I took it as seriously as I did. Even then, I ended up having to call the SES, although thankfully I was able to walk myself out. It’s definitely not a route to be underestimated.

If you are similarly paranoid, then you might enjoy my highly-opinionated trip planning guide for this track, or this interactive map that I made using Felt.

I’ll be leaving Australia soon, so above all, this is my swan song to the Victorian Alps. It’s a lot, I know — I mostly wrote it for me. And for Scott’s dad Alex, who once boiled me six eggs, and also gets lost in the bush sometimes.

Here goes.

Track Notes

From Mount Howitt to the Viking, the Viking Circuit traces the Great Dividing Range, before descending south to the Wonnangatta River, on the traditional lands of the Brabralung clan. On paper, the Great Dividing Range serves as the boundary line between Taungurung Country and Gunaikurnai Country, but as an ongoing result of colonial violence, dispossession, and dislocation, the process of determining custodial ownership and boundary lines is not always straightforward.

Colonial maps attempt to represent tens of thousands of years of history, stories, and relationships as static lines — lines that do not necessarily account for how Gunaikurnai and Taungurung peoples have moved and travelled and come together across river valleys and the ranges, over thousands of generations.

In the years since, Gunaikurnai and Taungurung representatives have jointly finalised negotiations over a boundary agreement, which recognises Taungurung as the Traditional Owners of the northern slopes of the Great Dividing Range, and Gunaikurnai as the Traditional Owners to the south.3This agreement includes joint management of the Alpine National Park, in which the Viking Circuit is located. Gunaikurnai people are the joint managers of fourteen parks and reserves in Victoria including the Avon Wilderness Area and Baw Baw National Park, as well as the parts of the Alpine National Park on Gunaikurnai Country. Taungurung people are the joint managers of nine parks and reserves, including Mount Buffalo National Park and Cathedral Range State Park, as well as parts of Kinglake National Park and Alpine National Park.

Like many people who venture into the Victorian Alps, I enjoy walking in very remote areas because I like to be alone. But I don’t want to perpetuate some insidious delusion of a frontier explorer. Even though I might feel isolated out there in the bush, I did not just happen upon virgin, ahistorical territory. I’m a visitor there, and my presence is not one I can take for granted.

I’m a second-generation settler migrant. My family is from the north shore of the South China Sea, and I was born in Melbourne, on Wurundjeri Country. I’m hesitant to claim either as home, but I’m okay with the ambiguity. It reminds me where I am, who I am, where I come from, and how I am connected to everything.

Trip Report

Howitt Carpark to Macalister Springs

Day 0: Saturday 11/11, 17:50-19:00 (~5km)

It’d been a rainy week, and I was having second thoughts about driving my hot hatch up Tamboritha Road and Howitt Road. I called the Heyfield DEEC, who confirmed my suspicions. Although Howitt Road was open,4It was not the last time I went up that way in December 2022. they reckoned Tamboritha Road was pretty rough.5See also: Road Conditions.

My partner6This post has taken me so long to write that we’ve since broken up but if I did replace all mentions with ‘my ex’ it would probably create more cognitive load for the reader — and also for my self — so I’m just going to…leave the wording as is since it’s not hugely relevant in the grand scheme of things for anyone but us, and we were still together during the time period about which this post is written. had been gently (and then somewhat more firmly) suggesting that I accept a ride to the TH7This means ‘trailhead’ if you’re a dickhead, or ‘I’m a dickhead’ if you’re not. in the Land Cruiser, but I wasn’t about to give him an excuse to crash my birthday party. He tried a different tack, and suggested I borrow my dad’s Land Rover.

As reluctant as I always am to drive an automatic car, I ended up being very glad I did; there were some sections where I do believe I could have crawled over in first gear, but I really really would not have enjoyed it if I had been in my own (stiff, low) car.8 Also, just because you can make the trip in a 2WD, doesn’t mean you should. That same car ‘made it’ up Tamboritha Road in 2022, in the sense that I did not get bogged or stranded, but then I had to spend a grand replacing my front shocks. Correlation does not equal causation, and I’d be lying if I said I’d never done a single other thing to compromise my over-engineered German suspension, but…it’s a probable culprit.

I rolled into Macalister Springs with ample time before sunset. There were a few groups near the Vallejo Gantner Hut, and another group down next to the Springs. I camped alone in a secluded clearing a couple minutes down from Mac Springs with an excellent view of the next few days’ walking.

Macalister Springs to Mount Despair and the Razor

Day 1: Sunday 12/11, 06:50-19:10 (~22km + ~4.5km)

I woke up in time for dawn. And uncontested use of the designer loo. After a brief waffle around the hut where I searched in vain for a water tank,9At a campsite named for its natural water source, no less…I have nothing to say for myself except that I’m not a morning person. I was on my way over the Crosscut Saw.

Despite — and because of — the perpetual threat of dense fog, high winds, blistering cold/sun, and toppling off into the abyss, the Crosscut Saw is one of my favourite parts of the High Country. It’s good clear walking along the ‘scenic rim’ of the Terrible Hollow, and it’s very motivating to look across and see my progress.10I have about a billion shots of the Razor from slightly different (but mostly the same) angles to prove it.

It’s only relative to the rest of the Viking Circuit that I can describe the section up to Mount Speculation as ‘easy’ walking. By this I mean it is still bloody hard by most metrics — but the tracks are usually clear as they receive much more traffic,11Between Mount Buggery and Mount Speculation, I bumped into about 30 people all on their way back from Mount Spec. As the only person heading the other way, I pulled over by default unless someone insisted they needed a break. Unfortunately I ran out of people for whom to stop by the time I reached the climb up to Mount Spec proper. you don’t really need to navigate, and you’re walking from one reliable water source to another.

I was up and over Mount Speculation in time for lunch. Camp Creek was running well; in fact, it seemed to be running all the way across the track. It was based on this observation (and the rainy week preceding) I hazarded only a modest top-up of my water reserves. I left Camp Creek with enough to dry camp at Mount Despair and make it to Viking Saddle the next day.12Technically correct — it was after Viking Saddle that I had problems.

I took the old Speculation Road to Catherine Saddle as a reprieve from the tightly packed contour lines I’d been doing all morning.13The old Speculation Road 4WD track is flat and not very scenic, but that was fine by me; I was busy with my usual preoccupation of “is this a very snaky stick or a very sticky snake”. It’s not a particularly challenging or interesting section, but as someone who is regularly reminded that people can drown in puddles, I gave it proper caution. See also: Decision Points.

After a few kilometres of picking my way across ruts and rocks, I was at Catherine Saddle and partaking in my favourite on-trail hobby of glaring at the elevation chart and expecting it to be different from the last time I looked at it. Seeing as it had not changed at all, I elected to stay the course with my water strategy, and regrettably did not venture back onto old Speculation Road to top up.14See also: Water Sources. I would not be punished for this decision just yet; rather, I spent the rest of the day feeling quite grateful for it.

The climb out of the saddle was particularly heinous, and the subsequent descent all the more so for the fact I’d been expecting the Mount Despair campsite a lot sooner. After a lot of “is that it…no can’t be” at every flattish ellipse draped with branches auditioning for Lady Macbeth, I finally arrived around 15:15 — no later than I’d originally planned, but somehow after having walked further than I expected.15Every time you dare to ask, “Are we there yet?” it probably adds another 5km.

Given the early hour, I was still entertaining the possibility of pushing onto Viking Saddle, and I’d been deferring the decision until I arrived at the Mount Despair campground.

I would’ve made it to Viking Saddle if I’d left immediately, but I was not in the mood to initiate on such a decision by the time I finally arrived at the Mount Despair campsite. I wouldn’t usually be so wiped after barely 20km, but I’d been properly humbled by that day’s walking.

Let’s split the difference and concede that since it was the eve of my birthday, I did it in service of the poetic flourish of climbing out of Despair and over the Viking on the morning of my birthday.

I settled on doing an out-and-back of the Razor (~4.5km) as I doubted I’d make it up there otherwise. Loaded up with a hipbag including a torch and that night’s dinner, I made good time across the mossy rock bands and scree fields towards the Razor. The wayfinding was getting a bit harder, but I was reassured by many more pink ribbons, cairns, and AAWT markers flapping around in this section.

Now, I love a rock scramble (probably more than most hikers; I’ve since gone all the way and taken up full-frontal rock climbing), but not on red shale. Every single bad thing that has ever happened to me out in the Alps has been because of that crumbly purple devil rock.16That rock is actually a lot like me while doing a multi-day pack carry! It does not want to be load bearing. It is actively decompensating. It is in the middle of a breakdown and it would appreciate it very much if you could nick off and leave it the hell alone.

Unlike many other boulder fields, it eventually becomes possible to identify a footpad across red beds because red shale wants to disintegrate into a chalk outline for your corpse.

My GPX alleged if I just went straight on up I’d eventually reach the Razor. Around 18:10, I crawled out from a hammock of scrub after having independently verified the GPX was, at best, optimistic.

Definition: The sound your mouth hole makes

as you let go, let god, let gravity.

Synomym/s: Talus.

Unlike the guy who said he completed the last two days of the Viking Circuit with a dislocated knee after the Razor, I was not quite shameless enough to explain to the Garmin emergency dispatcher that I’d followed the GPX straight into a ditch, no questions asked, so instead, I parked myself in view of both the Razor and the Viking for a quick dinner as the sun set.

In anticipation of my dry camp that night, I had brought along the type of food you’d never in good conscience consider if you had even one other choice: a Colesworth17I saw someone in r/UltralightAus refer to ‘Safcol’ and it blew my mind. foil baggie of tuna and chickpea salad.18I acknowledge this as one of my most ‘toxic bachelor traits’, i.e., using my monthly Woolworths 10% off discount to stock up on the most atrocious shelf-stable ready-to-eat supermarket food known to mankind.

I had a bit of 4G up there and briefly considered Googling “razor viking site:bushwalk.com” for the beta, but it was too late to make a real attempt of it. Instead, I looked up the Heyfield IGA opening hours and fantasised about all the food I wanted to eat at the other end.

Mount Despair to Wonnangatta River

Day 3: Monday 13/11, 07:30-17:50 (~13km)

I woke up another year older and retraced my steps back towards the turnoff for the Razor, and then beyond to Viking Saddle.

On my way, I bumped into the counter-clockwise group I’d been expecting since I signed in. They’d started the same day as me, and were now on the final stretch after getting “the worst part out of the way first”. I expressed my hope that they’d perhaps managed to bash a bit of a path through the next section; they regretted to inform me that they doubted it very much.

The track between Mount Speculation and the Viking outcrop is definitely rougher than the track up from Mount Howitt, but if it’s been cleared recently, then it’s relatively good walking, albeit fuck-off steep. The decline towards Viking Saddle was so sharp that it didn’t even hurt the few times I stacked it; the ground was already angled that close to my butt that it wasn’t very far to fall.

I’m typically fanging for a descent up until I get to the top of the climb, at which point I immediately remember how much I hate descending.

I was about to do it some more: two fruitless descents down both sides of Viking Saddle in search of water.

The day before, I reasoned I had enough to dry camp at Mount Despair before making it to Viking Saddle the next morning. It was now the next morning, and I had indeed made it to Viking Saddle with water to spare.

The day before, I reasoned I had enough to dry camp at Mount Despair before making it to Viking Saddle the next morning. It was now the next morning, and I had indeed made it to Viking Saddle with water to spare.

But it was only 11am, and I had only 1.2L for the rest of the day. I spread out my tent to dry19What on earth was I thinking…that was FREE WATER!!! and stood around choking down a SaltStick with half my birthday brownie, contemplating my hydration strategy for what was already a very sunny day.

I was (un)reasonably optimistic that although I would definitely be dehydrated, I probably wouldn’t die as long as I made it to the river.20I hate to think what would’ve happened to my kidneys had I not made it. While the section over the Viking would be exposed, I knew I’d be descending back below the treeline. Who knows, maybe there’d even be water on the way?!

For now though, it was hot and exposed. And hilly. The climb out of the saddle did not make me feel much better, but at least the Viking was once more in view! I forgot everything I hated about descending as I told myself this was the last big climb; it was all downhill after this.

After reading so many trip reports, it had not even occurred to me to be worried about the crux of the circuit until the counter-clockwise group suggested I might have a hard time getting over it alone. So it was a good thing I didn’t get to spend long worrying. And an even better thing that I did not spend very long getting over it either.

Perhaps in other years, at other times, or from another direction, it is more or less difficult to get over the Viking.21See also: Section Notes. On this occasion, the track led me right to the rope dangling down the rock chute (also known as a ‘chimney’). I climbed through the first hole with my 45L pack on, only to get briefly strangled by my hat trying to get through the second.

I was on the Viking a little past noon, and promptly burst into tears because there was nothing else for it. I don’t know if anyone else does this — or if it’s one of those things we’re not supposed to admit because we’re meant to have some more pride — but sometimes the sunlight hits a cloud in a very good way, and that’s amore I am so spellbound that I must have a little weep. It feels a bit silly saying this but I also believe it is only normal and human to feel humbled and awestruck by the excellent sights I get to see.22 If this has never happened to you then have you considered getting out more?

Despite all the hills I’d climbed and descended to get here, I was very satisfied having made it up there in time for my birthday. Looking down upon all those Tobleronis helped to give context for my suffering. I had a little snack and replied to some birthday messages to shore up strength for the oncoming scramble. I was expecting the track conditions to deteriorate dramatically after I turned off from the AAWT.

The track does indeed get blurry where it departs from the AAWT, but this was probably my favourite section for as long as it lasted. I enjoyed the next bit of rock hopping towards South Viking. This is my favourite type of terrain, even though I once cried on the Ferris wheel.23I remain very afraid of heights, which is apparently why I keep putting myself in literal life-or-death situations involving heights.

Navigationally, it had become much less straightforward, but it was still manageable. It was the level of challenge I’d been looking forward to, and if the entire trip had just been about intuiting a good line across a rock band, or keeping an eye out for a hard-won cairn,24It was not. then I’d have enjoyed that very much.25I did not.

The fellas from that morning had said they thought it might be better to do the South Viking downhill, and with the hindsight of having done the Old Zeka Track uphill, I can agree. Having the ridgeline as a reference point was useful in navigating between or around the sections of the track that I did manage to find, and the decline was proprioceptively noticeable enough that I had one clear direction to move in. This is a section where you will be well-served by paying attention to the lay of the land.

The track reemerged (albeit patchily) after the decline steepened, and then it was just a matter of putting one foot in front of another. It likely would’ve been tolerable after that had I not been dehydrated, delirious, and decompensating.

As the river came within earshot, I noted with no small amount of hysteria the yellow spray paint arrows directing me towards the campsite. This was definitely not the part I struggled with; in fact, it was the most amount of ‘track’ I’d seen since the climb out of Viking Saddle.26I’ve since seen in other accounts that the section right before the river can get especially overgrown with blackberries and difficult to navigate, so I imagine future walkers may have cause to be more grateful than I was that particular afternoon. See also: Section Notes.

It was a long, hot day for rationing water, and I found myself cycling between numerous apps (compulsively, every few hundred metres) to find the least dismal projection for when I was due to hit the river. My Garmin reckoned I was frolicking at a humble 1.5km/h, although occasionally I apparently stepped it up to a riotous 2.4km/h.

It was a good thing the campground was empty when I finally burst into the clearing, because I was in high dramatics by then. I ran down to the river, filtering water directly into my mouth and generally carrying on like I was dying of thirst.

Having survived a very difficult day, I was looking forward to tomorrow being my last.27At that point, I had no reason to expect it would get much worse than what I’d already endured; in fact, I anticipated being much more resilient to the upcoming bushbash, having replenished my water supplies so amply.

Erroneously believing I’d already endured the worst of it, I was in relatively high spirits that evening. I’d saved my last hot dinner for this night, and finished off the rest of my birthday brownie with the singular teabag I’d brought along. Happy birthday to me!

Wonnangatta River to Howitt Carpark via Old Zeka Track

Day 4: Tuesday 14/11, 08:25-22:10 (~18km)

I am generally okay at sleeping alone in the woods, provided I’m actually alone.28Wildlife and incorporeal entities notwithstanding. I could never claim to be a good sleeper even at home, but I’ve settled on a tried-and-true compromise when I’m feeling nervy about being alone in the woods:

- Walk from dusk til dawn without pause until absolutely demolished.

- Drop pack at the most isolated campsite possible.

- ???

- Pass out.

Sleeping alone in the woods and being suddenly beset by random human strangers in the middle of the night, not so much. I don’t know how anyone can ever be okay with that. I don’t think I’d be okay with it even if I were the arriving stranger.

At around 2am, I woke to the sound of twigs being crushed underfoot — okay, fine, the worst/biggest thing it could be is sambar, maybe wild dogs — and then — nope, it can get worse, this is worse, guess I’ll just die — lights and voices. After a brief moment of panic, I tried to calm myself by reasoning they were either doing an FKT,29And I don’t think FKT records are made on attempts where it takes you until 4am to finish blowing up your mattress. So I guess we were all three of us unhappy campers that morning. or else they’d had a way worse day than the one I had.

By the time I emerged from my tent the next morning, it was two hours later than I’d intended to leave, and drizzling. Having aged an entire year only the day before, I was feeling all the more worse for wear for the sleep I’d lost. I’d made the unfortunate decision to dry some clothes outside overnight so I set off cold and wet both inside and outside of my rain shell, hoping that the merino would dry out as I got moving.

Unlike the counter-clockwise group, I’d intended to leave the worst part of the trip for the very end; I’d much rather feel relieved about going home. And I had a lot to look forward to, as it was already shaping up to be a punishing day.

I managed to find a footpad leading to the river. At the time the river level wasn’t high enough for me to give me pause even if it had been a false lead. I crossed the river at about calf-height, then crossed some other minor tributary again…and again?! What with the rain and the fallen trees everywhere, it was near impossible to discern a track.

I was relieved when I finally made it onto Zeka Spur Track. Situated as it is between one uphill bush bash and another, I don’t know what kind of masochistic ingrate I’d have to be to feel anything but thankful for the short-lived reprieve.30Having done only a part of it, I still rate this as one of the most straightforward and predictable sections of the entire circuit. I imagine I’d feel differently if I’d chosen to walk the entire thing, or if there’d been any 4WDs on the track. See also: Decision Points. For all the griping I’d seen about this track, I was just happy to maintain a decent clip for the first time in a long time without having to do any off-track parkour. Almost like ‘normal’ hiking!

It being wet, early, and a Tuesday, I was feeling pretty lucky to have made it to the turnoff without seeing a single car the entire time I was on the track.

I spotted a pink ribbon a couple turns before I expected to leave the Zeka Spur Track, but held on until I saw another pink ribbon where I expected one to be. I walked straight into the bushes with total conviction, at which point a convoy of 4WDs crawled past just in time to watch as I got stuck in a tree.

A girl gave me a thumbs up from the passenger window and shouted, “Cool!” like it’d made her morning to see a crazy person wrestling their CCF mat out of tree branches. You’re welcome, I guess.

The actual turnoff for the old Zeka Track was a little further down. I can’t for the life of me think why I decided to turn that early aside from seeing the pink ribbon, but I’m not quite committed to it being entirely my fault either. I feel like this may be some weird GPS dead spot.

The actual turnoff31Okay I actually don’t know if this was the real turnoff, or if any of the previous pink ribbons would have gotten me onto the track. I did find it strange that there were no markers here. was also not marked by any ribbons or cairns — and maybe I should have taken that as a sign to stay on Zeka Spur Track and take the long, boring way back — but it should be clear once you’ve found it because it does resemble an old 4WD track, and not Sleeping Beauty’s front lawn.

The rest of the old Zeka Track has definitely been cursed by some very angry fairies. I made piecemeal progress by repeating my strategy from yesterday’s bushbash of picking a bearing between two markers32Aim to the left of this tree, and to the right of this other tree that looks very much like it! and following sambar tracks around massive fallen trees.

If all scrub is equally dense, then don’t bother expending the mental energy to plot an equally overgrown route, lousy with obstacles of your own choosing. You can’t blame the track for being in bad shape if you’re not even following it. You will not find a shorter, faster way.33I won’t suggest this eventually puts you on a clearer route, or that it gives you a fighting chance of moving faster than 2km/h. Only that tripping on a rock underfoot is the only reminder you have that even though you are currently freezing, wet, afraid, and alone in the woods, that at some point, someone else was here. They tried very hard to keep this track clear for you, like a lifeline through time, and even though their success was thwarted by fallen trees, their effort means they imagined you here today, just as you honour the memory of their being here once too. Tiny violin for me, the ancestors, and the ghosts of hikers past.

Some parts were deceptively clear, and I briefly — or not, judging by the ~18km I somehow racked up on this day; I clearly lost a lot of time, body temperature, willpower, critical judgement, warmth, and energy here — entertained a shortcut, thinking it would make little difference since following the track seemed just as difficult. I eventually gave up on this and tried to stay as close to the GPS track as I could.

If all the highs and lows of the Viking Circuit so far were condensed onto a heart rate monitor, I’d now reached Code Blue cycles of peak elation/devastation for every time I’d follow a track for about ten metres, and inevitably have to take another massive detour around fallen trees.34If you’ve ever been so hungry and exhausted and cold and wet that you’ve been reduced to stomping your foot and crying a little out of frustration, then you can imagine where I was at, mentally and emotionally.

The day before had been slow, made slower because I was hot and dehydrated. This day was even slower, and slower still because I was cold and drenched. It had been drizzling all day, and visibility was low due to fog.

I had the presence of mind to notice I was feeling the effects of the cold quite significantly, with no improvement. Although I didn’t feel hungry, I forced myself to stop for lunch and tried to eat everything sugary and fatty I had left in my pack. I put on some extra layers and then made the perverse decision to change my socks even though I was wearing trail runners that soaked through again immediately.35Clearly I was so out of it that I attributed my wet cold feet to the river crossing, and not the subsequent hours tramping through dense dewy scrub in heavy fog.

I was pretty confused and scared at this point. I’d started the day fatigued, and the day had been a steady accumulation of worsening conditions. Aside from the brief stint on Zeka Spur Track, I was never moving fast enough to get dry or warm. I’d made so little progress that I didn’t realise how much time had passed. It’d been overcast and gloomy all day, but the closer I got to the top, the harder it was to see through the fog.

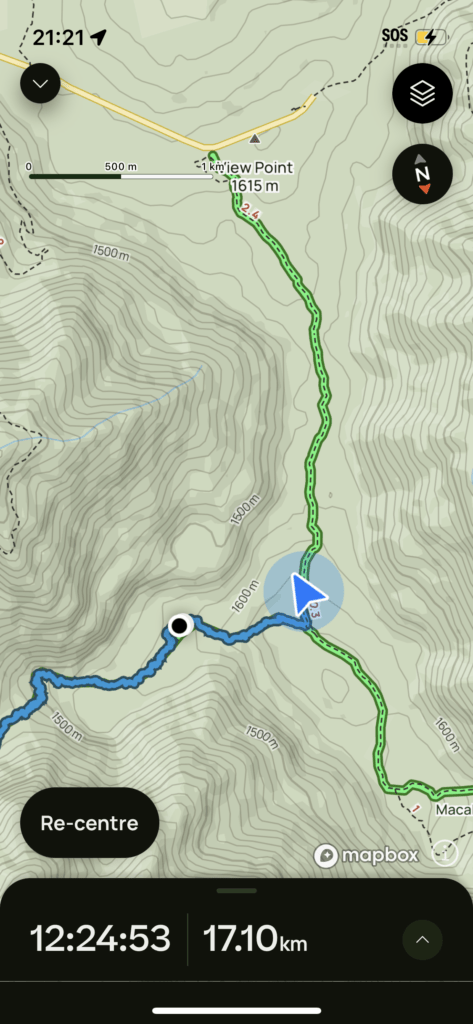

I’d left a trip intentions form with my partner claiming I’d be back at the carpark by 5pm, but by 6pm I still hadn’t reached the turnoff for the Mount Howitt Walking Track.

While the ship had clearly sailed for my critical judgement, I was still alive enough to panic about hypothermia. I stopped to make a hot drink36I know this sounds like nothing, but I had to have been very cold and very worried about it to actually put my pack down and do this; I do not like to stop during the day. Even when I do stop, most of the time I won’t even make myself a hot dinner! I only stopped to do this because I reasoned it’d help me get on my way, so it was still better than stopping altogether. and sent out a preset message via my InReach to say I’d be late.

It being my last day, I had it in my head that if I just grit my teeth and continued to walk in approximately the right direction, that eventually it’d spit me back out onto the track.

I had two hours until the sun set. I wasn’t in full panic just yet. I’d read somewhere that if you’re wondering if you should press the SOS button, you should ask yourself, “Am I certain of the outcome?”

And I thought, well, yes I’ll be fine to walk back to the carpark by torchlight, which left me two hours to make it a few hundred metres to the turnoff. Surely there’s no way I can’t make 200m in two hours!

Typing this out in retrospect, I should concede I was full loopy by this point. When I messaged my partner that I was calling the SES, the first thing he said was that I should stop there and set up camp. To me, that sounded downright dangerous, but only because apparently my tent and sleeping bag were so ultralight I forgot I was even carrying them.

According to the GPS, I was so close! Being able to locate myself on a GPS somehow convinced me that I was not ‘lost’, just ‘slightly off track’. In retrospect, this was probably the first time I’d ever truly been lost in the bush,37i.e. I did not know where I had gone wrong, nor which way to go next. which is probably why I was stubbornly refusing to accept that being 200m away from the turnoff means nothing if you cannot traverse that terrain safely.

The mechanism for the power button on my InReach had been bugging out since the second day so I hadn’t been able to turn it off. The cold meant the battery was almost flat. Fumbling around with the device forced me to notice exactly how laboured and clumsy my movements were becoming. I wondered if an actual hypothermic person would be able to recognise the signs of impending hypothermia. Then I wondered if my denial of my possible hypothermia was a sign of hypothermia.

At some point I must’ve frightened a deer, because something made a terrible honking sound that frightened me so much that I let out an equally terrible screeching sound that probably frightened the sambar again, such that we each spent an intense few seconds making terrible sounds (honking, screeching, and so forth) into the night.

I have to admit that it wasn’t any cogent grasp of the situation that compelled me to make the call. One sambar honking was just about enough for me. I made the call.38I hope you never need to use this information, but fyi you can get enough reception on the Telstra network up there to make a phone call to emergency services. It’s patchy though, and it’ll eat your battery. SMS works much better.

For hours, I’d been talking myself out of making the call, thinking I’d somehow make it to the turnoff before dark. I had felt so sure I could make those last couple hundred metres in the two hours I had before the sunset. And now it had been two hours. It was dark. And I had not made it.

My partner, noting I was “not very coherent”, left immediately from Melbourne, 6 hours from the Howitt trailhead. The Sale police also started driving up, 4 hours from the GPS coordinates I’d last sent. I don’t think I was capable of any other good decisions after that point. Against their better judgement, I was still insisting I could make it to the turnoff.

I won’t pretend it was a good decision, but I can also see how I would’ve gambled on ‘keep moving’ over ‘stop moving’. I was also a bit beyond the level of coherence required to even follow such a basic instruction.39The level of granularity I needed was a bit more along the lines of, “Do you have a shelter? Put your pack down. Open your pack and get out your tent. Can you set your tent up? Do you have a sleeping bag? Get your sleeping bag out,” and so on. Unfortunately, I no longer had the executive functioning to come up with all of those steps myself, so I just kept telling the Sale police that I wanted to try walk myself out, while thinking to myself, “How could I possibly stop?! If I wait four hours out here I’ll die!” In my state of mental depletion, my options had been reduced to: a) keep moving, don’t stop, somehow get out of here through sheer willpower alone, anything is better than stopping here, and b) stop moving, get too cold, die. 40It was a false dichotomy. It was absolutely not inevitable that I would make it out; that was not within my control at all. If it had been, I would’ve been out already; that was what I promised myself more than two hours ago. If anything, I was increasing my odds of continuing in entirely the wrong direction, running out of battery, getting injured, getting trapped, becoming severely hypothermic, or becoming severely dead. And I wasn’t even wearing anything that would make me an easy corpse to find.

By the time I finished my call with the Sale police officer, it was fully dark. Making that call somehow gave me enough of a push to keep going.41Or I was just worried my partner would finally make real on all the times he’d threatened to rescue me on his dually, now with a police escort.

Turning on my torch was a bit like driving through fog and drizzle with high beams on, i.e., not really that helpful. Nonetheless, the torch beam created a kind of mental ‘tunnel vision’, forcing me to focus on the section of impenetrable scramble immediately in front of me, rather than being overwhelmed by the equally impenetrable scramble everywhere else. I set a bearing, ploughed through/over every single thing in my way, and somehow made it those last 200m back onto the Mount Howitt Walking Track.

I’d spent over two hours on that last 200m. In the end, it only took me twelve minutes to walk it. Not for the first time that trip, I burst into tears upon arrival. Tripping over myself sobbing and sniffing, as I stumbled down the track through the rain was decidedly less majestic than scaling the Viking, but no less existentially transformative.

The police were able to turn around after they confirmed I made it back to the carpark, and I rolled into Licola at 2am, shortly before my partner arrived after driving all night from Melbourne, indeed with a dual-suspension mountain bike secured to the rack.42One time he rode my pack up Mount Stirling on a gravel (road-adjacent, racing spec) bike (that cost more than my entire car), so I have no doubt he would actually make good on the promise to rescue me despite all my protesting. Another time he tried to justify an upcoming dirt bike purchase by explaining that he would be able to use it to rescue me. I do not know how worried I should be that he’d ever believe I need to be convinced a dirt bike is a good idea — I have frequently been tempted to buy a dirt bike (less of a dirt bike and more…whatever the hell that dinky little Motocompo scooter thing is that comes pre-packed with the Honda City) and I don’t even know how to ride one — or how worried I should be that he also seems to believe I am perpetually in need of rescue. Somehow I do not think the optics have been much improved by this recent escapade.

He did not say, “I told you so,” even once,43Far less gracious am I, since I likely went on a tearful tirade about how there were trained, well-equipped professionals on their way, and how dare he risk his life. and instead just slapped my birthday present (that I did not in that moment particularly feel as if I deserved) into my hand with a long-suffering sigh,44May we ever remain so dear to our loved ones as to deserve being yelled at upon our safe return. May we persist in deserving their love by acknowledging our wrongs before they have to! and started unloading supplies to make me dinner (that I also did not in that moment particularly feel as if I deserved, but knew better than to protest).

I was very lucky I didn’t have to learn a harder lesson than the one I already did. It did mean a lot to me that I managed to walk myself out in the end, but I don’t fancy my chances of being rescued at all if I had left it any later. I got caught out by bad weather/track conditions, but most of all, by my own equally bad decisions and deteriorating mental state.

Even though I kept doubting my situation was ‘urgent’ enough to warrant calling emergency services, I’m so thankful I finally admitted to myself that I was struggling to keep a clear head, and made the call when I did.

Talking to someone and knowing they were coming for me helped me to regroup for long enough to grit my teeth and power on through the last 200m in twelve minutes where I’d previously spent over two hours stumbling around lost and cold. I’d never before appreciated the psychological boon of knowing there was someone out there who was coming to help me — and how much this lifeline helped me help myself.

So much of hiking for me is about getting away. I never realised how much I took for granted that I would always come back. And I’m kinda glad I realised that I really, really wanted to.

Post-Trip Reflections

There were many opportunities where I could have made better decisions for my own safety and wellbeing. I hope this retrospective on my mistakes can be a useful data point for other people who are considering this walk. 45I hope it doesn’t put anyone off! Or conversely, become some morbid fixation for anyone like it kinda did for me…

Up until now, I’ve managed to brute force my way through a high degree of discomfort and suffering. But because I was expecting a challenge, it meant I was worse off — how do you know when to call it?

This trip is not the first time I put off hitting the SOS button when another person might have pressed it long ago. I can concede to a bit too much resilience against suffering on a track — a bit of overconfidence, even, because of all the times I have somehow made it back.

But I did make the call this time — as my partner said, “it could have been fatal” — apparently that’s how far I have to push myself before I stop believing I won’t make it out alive by my own power, brute force or otherwise. It’s a fine line between being self-aware enough to know I need to call for help, but not quite self-aware enough to know when I’m making a bad decision by continuing to blunder around in the dark, completely lost and dangerously cold.

When I ask myself, “Am I sure of the outcome?” what I really mean is, “Can I exercise any significant control over this situation through willpower alone?”

If I’m cold enough to start getting very confused and clumsy, then directing my willpower is about as effective as a Koenigsegg engine when you’re asleep behind the wheel.

For the most part, I do believe that my experience could have been entirely avoided, or at least better managed. Hence the grisly post-mortem.

Also, I’m clearly awful at being the object of rescue.

Mistakes Were Made: A Post-Mortem

I’ve had ample time to reflect on this wayward experience — I started this entire blog for the purpose of doing so — and it comes down to the fact that I left myself too narrow a margin for error, so I couldn’t afford for much to go wrong.

And quite a few things went wrong. By the third day, it was a compounding clusterfuck of bad conditions and bad decisions.

- I was more fatigued than I’d expected because a) I’d spent the previous day quite dehydrated and b) I got woken up in the middle of the night and couldn’t get back to sleep until hours later.

- I started the day cold and wet, expecting to get warm as I kept moving and the day heated up. I might’ve had a much better time managing my mental state and energy levels on an already gnarly track if either eventuated. Neither did.

- Visibility was poor due to fog, and the rain did not let up all day. The track would’ve been hard to navigate even in fair weather, but it’s even more difficult to identify faint signs of a track/thoroughfare when everything is wet.

I’ve done a fair amount of off-track bushbashing and navigating, mostly on my own, but also with other people.46In fact, I’d never hiked with other people and never wanted to until I decided to do this track — I made a point to seek out more experienced bushwalkers and joined them on day hikes to learn how they read the lay of the land and picked lines across terrain. I like to think I took my preparation seriously! I don’t believe Old Zeka Track on its own would have taken me out if conditions had been the same as they had been the day before. That being said, I will not blame the conditions — part of deciding to do any given walk is accepting that conditions may be bad.

So what went wrong? I can only conject in retrospect. If I had to zero in on the one reason things went so badly, it’s that I didn’t know how to stop. Or the posi-vibe growth mindset version of that statement: “I’m still learning how to better pace myself.”47As opposed to the Gattaca mentality: I never save anything for the journey back.

As someone who intentionally chooses to pursue such ordeals with delight, glee, and premeditation, I underestimated the psychological impact of spending multiple days navigating notoriously difficult terrain.

- I anticipated the psychological challenge to be resilience and endurance — I understood this to be the point of the trip, and neglected the possibility that this perceptual frame would potentiate risk-taking behaviour and bad decision-making. It really throws off your threshold for how fucked you are.48If I’m on Mount Stirling, I’m going to be on red alert if I suddenly come across an impenetrable thicket of regrowth. It will be very clear to me that I’m going the wrong way. But on the Viking? That’s what the track looks like, 360° all the way round. Or conversely, I’ve been on Mount Stirling in the rain, but all I did was put on my jacket and pick up the pace. It’d take an outright storm before I’d consider bailing for shelter and setting up camp. On the Viking, I vastly underestimated the extent to which I could be obliterated by a day’s worth of light drizzle. And there’s no shelter or road to bail yourself out to anyway, so why entertain the possibility? Because my expectations for difficulty were already so high, it’d have taken something a bit more extreme than drizzle for me to register that I was in danger. By the time I started to register this fact, it was because I was already too cold, and couldn’t warm up again.

- No matter how tired you are, it’s one thing to tough out an extra couple of hours when you’re dry and warm, and you can predict how long it’ll take for you to get to the exit. That’s why I kept telling myself I’d make it out — it’s because I’ve had enough similar experiences where I did make it out safely, even though it sucked. I ignored the fact that I was missing a crucial piece of information — when walking off-track, I cannot accurately predict how long it will take to traverse the distance. This made it impossible for me to safely manage my own energy levels and pacing.

- My tolerance for being ‘lost’ was completely blown out. For the two hours I spent stumbling around scared and confused, I was never very far from the track intersection. I knew I was approximately where I was meant to be, and my false confidence was bolstered by the fact I could see my position on a GPS device. It gave me the sense that the track would/could be just over/around the next tree. But all the trees — fallen or upright — were as tall as (if not taller than) me, so that information didn’t mean much in terms of putting one foot in front of the other. It meant even less as I got progressively more shaky and delirious. Getting over an obstacle was impossibly dangerous. Getting around meant I risked getting even further from the track. Even in the sections where I could, with great effort, push through, it exacerbated my fatigue, drained all the energy I had left, and inevitably led me to another huge obstacle anyway.

I treat everything like a sprint,49I often blame my total lack of stamina on being a powerlifter; “my performance time is measured in seconds!” When I deadlift, I don’t need to think about saving energy to put it back down — as long as I keep my hands on the bar, it’s IPF-legal. and then I get caught out because the race isn’t over yet. I left myself a very narrow margin for error, and totally precluded the possibility I would ever stop. So when it came time where stopping was the safest decision, the option did not occur to me at all. In my mind, the only way out was to power through.

Learnings

Prevention: How do I minimise the chances of this happening again?

- Build experience in safer contexts (e.g. with other people, on less dangerous/remote hikes). Keep everything else a controlled/known variable when I’m focusing on mastering something new.

- Ensure a larger margin for error/the unexpected. If a hike is both mentally and physically challenging, avoid maxing out on both, e.g. the Viking Circuit is still difficult over four days.

- Proactively account for a change in plans such that I’m always willing and able to stop/wait out bad weather. I already mark potential bailout routes (e.g. 4WD roads, huts, tracks to truncate the route). For routes with no such option, this might look like designating check-in points/decision-gates each day.

- Extra water is a safety consideration and my capacity to carry it a hard limit. The extra ~3L I should’ve carried would’ve been a significant jump as a % of my bodyweight. If I’d had this either/or decision-gate in planning, then I would’ve a) carried the water or b) stayed home.

- As hydrated as I’m planning to be on the inside, in the future, no more getting wet!!! If it’s cold enough for a midlayer, I’m not allowed to get wet. Too high risk. I carry Gore-tex mittens in the summer. What business do I have swimming in rivers?!

Mitigation: It’s impossible to guarantee this will never happen again, so if it does, how can I best help myself manage things next time (and help others help me)?

- Develop a framework to triage situations where I’m already confused, scared, fatigued, or stressed. Rather than relying on my own ad hoc assessment in the field, I can pre-define a prerequisite set of conditions to help me decide the threshold of an emergency, and next actions.

- Update the emergency protocol in my trip intentions form to empower my emergency contact beyond “call the cops and pick up my corpse please”. The current protocol is based on the most extreme circumstance where I am incapacitated and uncontactable, with the assumption that before that point, I’d hit SOS on my Garmin. In practice, this premise all but negates the need for an emergency contact. But my emergency contact is always someone who knows me very well, and knows how my brain works.

- e.g. Instead of telling me to “stay put”, my partner instead repeated the following: “You need a hot snack? Set up camp. Eat some food. It’s late. Rest.” Unfortunately, his perfect balance of granularity and concision was wasted on me. I just straight up didn’t parse any of it. Despite my efforts to ‘protect’ him from having to come rescue me, had I followed his instructions instead, I would have achieved just that. It was only because I kept ignoring him and rambling on like a crazy person that he was probably like, I guess have to drive six hours to make you a hot snack because you’re clearly not in a state to make one for yourself. Do you know how I can tell? It’s because you didn’t make even one joke about being a hot snack.

The White Whale: Completing the Viking Circuit Solo

I’d be lying if I said I didn’t choose to do the Viking Circuit because it was so notoriously difficult. I’d be lying even harder if I said I didn’t choose to do the Viking Circuit alone because I had something to prove to myself.

I’m relieved to have somehow walked myself out50Not because it mattered, at that point, to finish the trip the way I intended, but more because it was fucking creepy out there and I was cold and scared and wanted to feel agentic and in control somehow, so walking myself out seemed like a much more attractive alternative. — I know I would’ve come back for it again if not, even though I also know it would’ve been a bad idea. It’s like how they say to never take a university subject twice. But having done it now, I have nothing more to prove, and I don’t think I’ll ever do this again, at least not alone. If I was trying to prove the extent to which I can endure suffering, then I feel like I have more than earned my right to suffer much, much less.51Also I’m pretty sure everyone in my life who had to worry about me as a consequence of this experience would sooner pull the water pump out of my car than let me go again unsupervised, if not for my safety and wellbeing, then surely their own blood pressure.

Choosing to hike alone has forced me to develop many skills in a way I would not be compelled to in a group. But I would not understate the value of having people around to troubleshoot tricky navigational challenges, or an extra set of eyes on that errant broken branch or rock that might mark the reemergence of the track. Someone to spot you water if you have let yourself run out that day, or just to notice that you are definitely confused as all hell. Of course, they shouldn’t have to — no one should have to cover for you. We’re all responsible for ourselves. But things do go wrong, and in those situations, it helps to have other people around.

And I’m not exempt. At the very end, although I was physically alone when I walked myself out, it was only because I’d finally asked other people for help that I managed to do it at all. If I had left myself to my own devices, I don’t think I’d have summoned the strength or the courage to get out — nor would I have been cogent enough to set up my tent and make it through the night. I don’t think it would have ended up well for me. Do people die of cold overnight? What, like it’s hard? People do it all the time. In poorly-insulated urban homes at much lower elevations. Probably the meanest thing my partner said about the whole thing:52i.e. Not even a little bit mean at all. Much. “Don’t be a hero.”

It’s a difficult impulse to guard against — to an extent, the Viking wouldn’t be so attractive if it weren’t so damn hard. There are so many scenic walks in the High Country. It doesn’t have to be like this.53In fact, upon reflection, I am shocked and appalled that more people haven’t just decided to do it as an out-and-back — it solves the water issue, it all but removes the bush-bashing…in fact, I may do this version before I leave the country, just to prove this point. This craving is something we are looking to overcome in ourselves.54I try to be cautious about using ‘we’ because it implies certain things about the reader that I should not/cannot assume. But in this case I am hazarding a guess that you’re either reading this because you want to do this circuit, in which case you share the same perversion, or you are experiencing something vicarious through reading my account, in which case you have another kind of perversion. So. It was never the Viking.

Before I got transferred to the Sale/Heyfield office, I spoke to another police officer55He told me he was not familiar with the area — not sure why the emergency dispatcher connected me to him first, nor which station he was from. who asked me, “What are you doing? Are you just…wandering around out there? Do you do this sort of thing a lot? Walking around alone? Not very safe, is it?”

It’s definitely not the first time I’ve heard something like that, although it’s uniquely unhelpful and unsympathetic to hear when you’re stuck out on a mountain in the dark. I felt blamed and condescended and defensive.56In my fragile mental state, I felt so desperate and defeated that I wanted to hang up and free the line for someone else. Despite the urgency I felt then, I still didn’t want to be rude (heaven forbid anyone less than the ‘perfect victim’ call emergency services), so I could only grit my teeth and say, “No, I suppose it’s not,” even though I wanted to explain that I was not just “wandering around”, that I had tried my best to prepare for this trip, that I did do “this sort of thing” a lot, and that’s why despite the unfortunate circumstances, I could share with him exactly where I was if only he cared to ask me a question that actually mattered in this moment, like, “What are your GPS coordinates?” I especially don’t like hearing it because I know firsthand my partner576′ tall, male, spent enough of his childhood in FNQ and enough of his adulthood working in construction to pull out the most ocker accent whenever he wants to make me wince and/or squirm. doesn’t get the same reaction when he goes out into the wilderness alone. The police officer nonetheless had a point; there are risks to being alone. I lose any reference point for how far I might be from my own best judgement, especially if I’m hypothermic,58Hypothermia is the single biggest danger I can think of when it comes to hiking alone; it’s one thing to be alone and awake and aware and accepting of the fact that you are in a bit of a pickle (e.g. you have been bitten by a snake or you broke your leg), because at least you will be of sound mind and able to decide what to do next. It’s another thing to be alone and objectively in a pickle but subjectively in denial, because for whatever reason, you do not have the capacity to recognise the pickle for what it is (e.g. you somehow inhaled a metric tonne of poppy seeds or you have hypothermia). I’m somewhat higher risk for this as I prefer off-track, remote, or overgrown walking with high navigational difficulty or at least a decent amount of rock scrambling, have a tendency to turbo through dawn till dusk without stopping to eat a proper meal, and get cold very easily with no commensurate ability to warm up again. lost, or fatigued.

For the most part, I don’t seek company when hiking (the whole point is its opposite), but on this track, it might have even helped to have someone to commiserate/celebrate with, because this circuit fully sucks ass, but also, wow, look at you go!

My partner suffered numerous rejections each time he volunteered his company, if not out of concern, then at least to celebrate my birthday. I said no, not because I didn’t think he’d be able to do it (for a non-hiker he is frustratingly adept), but because I just didn’t think he would have enjoyed it.59If someone you love is a hiker and you have been invited to do the Viking Circuit, then I hope it’s because you’re known to be an avid hiker who enjoys a challenge. Because otherwise, there are only a few reasons that I can imagine they’d ever invite you:

a) they want to break up but they don’t know how, so they’re hoping you’ll do it for them if they subject you to enough suffering,

b) they don’t want to carry their own food up there, so they’re planning to consume you piece by piece,

c) they’re short, it’s raining, and they’re expecting to need a piggy-back across the river, or

d) they don’t actually know anything about the Viking Circuit, in which case you should definitely not go anywhere with them. I mean, I can’t even really say if I enjoyed it.

I have some additional thoughts on ‘enjoying’ yourself versus ‘suffering for the sake of filling the void’…but more on that another time.

And so completes my laundry list of learnings and opportunities to improve for next time. Of course, there is a part of me that is satisfied to have completed the circuit on my own, but I’m even more happy to be alive.

Somehow, I made it out to be another year older. Happy birthday to me indeed.

Leave a Reply